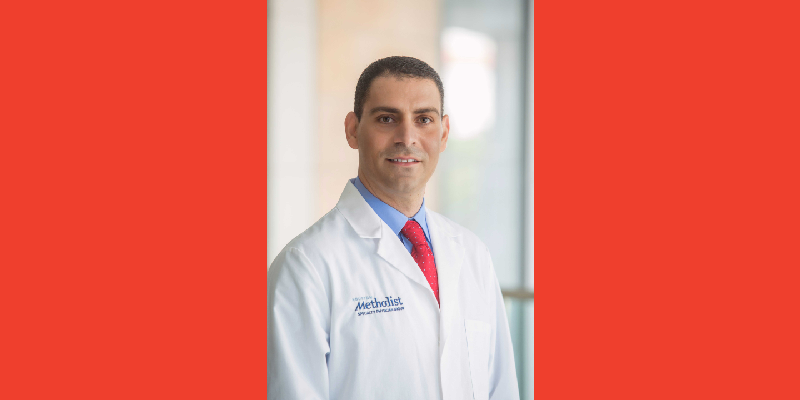

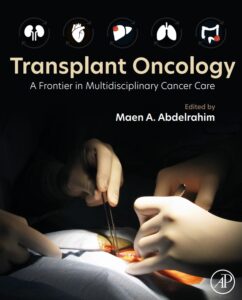

In this interview, Maen Abdelrahim, MD, PhD, of Houston Methodist Neal Cancer Center, discusses his pioneering work in the emerging field of transplant oncology, a rapidly evolving subspecialty that integrates oncology, transplantation medicine, and surgery to expand treatment options for patients with liver and other organ-confined cancers. As editor of the newly published volume Transplant Oncology: A Frontier in Multidisciplinary Cancer Care, Dr. Abdelrahim brings together leading experts from across disciplines to offer a comprehensive guide to this innovative approach. The book provides detailed insights into the rationale, patient selection, procedural considerations, and outcomes data that support the use of transplantation as a curative-intent strategy in select oncology cases. It also explores the latest advances in immunosuppression, cancer biology, and translational research that are reshaping how clinicians think about long-term cancer control.

Throughout the conversation, Dr. Abdelrahim reflects on the multidisciplinary collaboration required to make transplant oncology a clinical reality—from oncologists and transplant surgeons to pathologists and immunologists. He shares how his personal experiences with patients inspired the book, as well as his hopes that it will serve as a foundational resource for clinicians, researchers, and trainees looking to adopt or study this novel therapeutic paradigm.

—

In the book, you have described transplant oncology as a “frontier” in multidisciplinary cancer care. What defines this frontier, and why is now the right moment for this field to emerge?

Dr. Abdelrahim: Yes, now is the time. Transplant oncology is essentially the treatment of cancer through organ transplantation. We aim to cure cancer by replacing the entire organ affected by the disease, which primarily applies to liver cancer. This evolving field necessitates a multidisciplinary approach where transplant oncologists—also referred to as GI oncologists—collaborate with transplant surgeons, hematologists, and immunologists to maximize therapeutic benefit and potentially cure the cancer through transplantation.

This is the right moment because outcomes from transplant procedures were previously limited and often poor. However, when oncologists began working closely with transplant surgeons, outcomes began to improve significantly. This collaboration has led to increased survival rates for patients, especially through the use of better immunotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting—before transplantation—and comprehensive post-transplant care, such as adjuvant treatments. These improvements underscore the importance of a multidisciplinary team approach to enhancing patient outcomes in transplant oncology.

In the book, you highlight the use of immunotherapy in transplant recipients—a group often excluded from clinical trials. How are you navigating the balance between therapeutic benefit and the risk of rejection in these patients?

Dr. Abdelrahim: Nearly all clinical trials involving immunotherapy exclude transplant recipients or candidates. The main reason is the risk of organ rejection after administering immunotherapy.

However, this risk is not absolute. Over the past 10 to 15 years, as immunotherapy has become a standard cancer treatment, we have encountered patients with either a transplanted organ or those on a transplant list who might benefit more from immunotherapy. Through clinical experience and retrospective cases, we have found that rejection is not inevitable. For example, in liver transplant recipients, the rejection rate following immunotherapy is approximately 30% to 40%.

This leads to the critical question: What about the remaining 60% to 70% of patients who do not experience rejection? Why do they not reject the graft? This question has sparked significant research interest. We are now focused on identifying which patients are likely to benefit from immunotherapy and which are at higher risk of rejection.

To address this, we are investigating potential biomarkers that could help guide immunotherapy use after transplantation. Cancer can recur even after a liver transplant—for example, hepatocellular carcinoma or colorectal cancer with liver involvement. In such cases, immunotherapy may be a life-saving option. The challenge is determining who can safely receive it.

One emerging area of interest is the role of PD-L1 expression in the transplanted organ. Although not yet a definitive safety marker, PD-L1 is showing promise in helping to identify suitable candidates for immunotherapy post-transplant. If PD-L1 is negative on the graft, the patient might tolerate immunotherapy without rejection. If it is positive, the risk of rejection increases.

This is still an evolving area. Most of the data are retrospective, and we do not yet have strong prospective studies to guide us. However, we have treated post-transplant patients with immunotherapy. For instance, I have managed cases of melanoma in liver transplant recipients who lacked targeted therapy options. Those who were PD-L1 negative responded well to immunotherapy, experienced no rejection, and continue to do well.

These are limited cases, and we cannot generalize until prospective trials are conducted.

You discuss the role of ctDNA [circulating tumor DNA] in post-transplant surveillance and treatment monitoring. How close are we to ctDNA becoming a standard of care in transplant oncology, and what challenges still need to be addressed?

Dr. Abdelrahim: The use of ctDNA in GI oncology has evolved significantly over the past decade. It is already the standard of care for colon cancer. However, its application in other GI cancers, especially in the context of transplantation, is not yet standard.

There is growing interest in using ctDNA in the post-transplant setting for 2 main reasons. First, in cases like liver cancer, adjuvant therapy is often not administered after transplantation due to a lack of supporting data. Previous clinical trials in this area have failed to show benefit. Traditionally, we rely on tumor markers such as alpha fetoprotein, along with imaging, to monitor for residual disease.

There is growing interest in using ctDNA in the post-transplant setting for 2 main reasons. First, in cases like liver cancer, adjuvant therapy is often not administered after transplantation due to a lack of supporting data. Previous clinical trials in this area have failed to show benefit. Traditionally, we rely on tumor markers such as alpha fetoprotein, along with imaging, to monitor for residual disease.

CtDNA offers a more sensitive tool for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) within 6 to 8 weeks post-transplant. If MRD is detected, this could justify the initiation of adjuvant therapy, such as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, to eradicate residual cancer cells and delay or prevent recurrence.

The second key use is long-term surveillance. After transplantation, standard practice includes periodic imaging and alpha fetoprotein measurement. However, we were the first to publish on the utility of ctDNA in this setting, and our findings show that ctDNA positivity post-transplant is an early indicator of recurrence—often 2 to 3 months before imaging can detect it.

This early detection opens the door to curative interventions, especially in cases of oligometastatic disease. Early treatment increases the chances of long-term survival.

Therefore, ctDNA has strong potential in 2 areas: early detection of MRD and long-term surveillance after transplantation. We have worked on this for the past 5 years and have published our findings. What we need now are prospective clinical trials to validate these results and fully integrate ctDNA into standard transplant oncology care.

How has your clinical experience treating hepatobiliary malignancies influenced the development of this book? Were there any specific cases or insights that helped shape your vision for transplant oncology?

Dr. Abdelrahim: One case stands out. We have been treating hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for some time, and in 2020, immunotherapy emerged as a promising treatment. Multiple agents were developed and soon moved into the first-line setting. We wanted more patients to benefit from immunotherapy.

I had a patient with unresectable, initially non-transplantable liver cancer. I treated him with immunotherapy, and he had a remarkable response—almost a complete response. However, even when immunotherapy works well, it is rarely curative.

Given his response and cirrhotic liver, I brought his case to the tumor board. I suggested we consider transplantation during this window of opportunity, as his cirrhotic liver would not sustain him long term. Initially, there was hesitation. We monitored him closely, waited a couple of months, and eventually proceeded with the transplant. He did exceptionally well—no rejection—and he remains cancer-free.

That case was a turning point. It highlighted a gap between transplant surgery and GI oncology. With the advancement of systemic therapies, including immunotherapy and targeted therapy, there was an urgent need for standardized approaches and multidisciplinary collaboration.

That experience inspired me to write this book and gather global expertise. The book includes 26 chapters written by specialists from the United States, South America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. These contributors brought diverse perspectives to the emerging field of transplant oncology.

The result is a comprehensive reference for oncologists, transplant surgeons, hepatologists, and trainees. As the field is evolving rapidly, we are already considering a second edition in the next couple of years to capture ongoing advancements. The motivation for the book began with one patient, but the vision grew into a global effort to share knowledge and improve outcomes in transplant oncology.

Given your involvement with international societies, how do you see global collaboration shaping the future of transplant oncology research and practice? Are there regional models that others could learn from?

Dr. Abdelrahim: The world has become much smaller with the advancement of virtual technologies, allowing us to collaborate globally without being physically present. I am involved with the International Liver Transplant Society and the International Liver Cancer Association. Historically, these societies were dominated by surgeons. Now, we are seeing increased involvement from oncologists, hepatologists, and other specialists.

In February 2024, we held a consensus conference that marked the beginning of a more integrated, multidisciplinary approach. We discussed key topics and developed preliminary recommendations, many of which are addressed in the book. These efforts aim to improve outcomes for patients with complex liver cancers.

One regional model worth mentioning is the Milan Criteria, developed in 1996 by Professor Mazzaferro in Italy, which demonstrated that HCC could be treated successfully with transplantation. This model was later expanded in North America, South America, and globally, allowing more patients to qualify for transplant with defined parameters.

International meetings—such as those held by the International Liver Transplant Society and ASCO [American Society of Clinical Oncology]—are critical platforms for sharing expertise. For example, living donor transplantation is more common in Asia and other regions, and learning from those models helps improve access and innovation worldwide.

We hope this book and the growing field of transplant oncology will inspire other institutions and regions to invest in this space and continue building global momentum.

For trainees or early-career physicians looking to enter this space, what skills or interdisciplinary knowledge do you think will be essential to drive the field of transplant oncology forward?

Dr. Abdelrahim: It is essential for trainees to think beyond their subspecialty. We are becoming increasingly sub-subspecialized in oncology, surgery, and hepatology. While this focused expertise is valuable, it is equally important to understand adjacent fields and embrace a multidisciplinary mindset.

Trainees should seek out transplant oncology conferences, read relevant literature, and engage in collaborative environments such as tumor boards and multidisciplinary clinics. These are the settings where knowledge is shared, and patient care is optimized.

The field of transplant oncology will not advance through the efforts of a single specialty. It will progress through collaboration. This is an exciting opportunity for early-career professionals to get involved in a fast-evolving area and help shape its future.

What are some of the most promising genomic or immunogenomic strategies emerging from liver cancer research that could reshape transplant oncology in the next 5 to 10 years?

Dr. Abdelrahim: Next-generation sequencing and molecular profiling are playing an increasingly important role in cancer care, and their impact on transplant oncology is just beginning to unfold. Traditionally, we have selected transplant candidates based on clinical criteria such as the Milan Criteria. These have worked well, but there is potential to do even better by incorporating genomic information.

We are beginning to identify molecular signatures associated with better outcomes following transplantation. In the future, molecular profiling may be used not only to select patients but also to predict long-term transplant success.

This strategy is not limited to HCC. It also applies to cholangiocarcinoma and even colorectal cancer with liver-limited metastasis. The data are still emerging, and while it is not yet ready for widespread clinical use, the potential is clear.

Genomic and immunogenomic strategies will likely become integral to transplant oncology over the next 5 to 10 years, enabling more personalized and effective care.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.